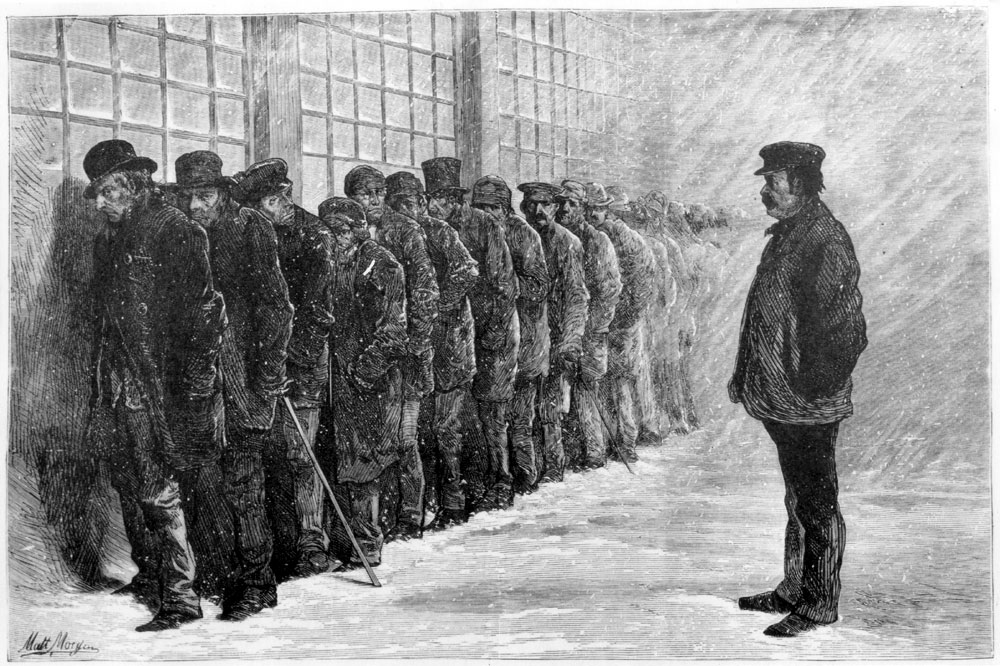

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered the first worldwide economic depression. In those days, they called it the Great Depression. It lasted for 23 years.

Long periods of stagnation and instability are recurrent in capitalism. We’re in the middle of the fourth one right now. And they happen because the system can’t maintain sufficient profitability.

When profits stagnate, so does everything else.

In a message to Congress in 1893, US President Grover Cleveland described the realities facing bankers, capitalists and workers during the original global slump:

… the speculator may anticipate a harvest gathered from the misfortune of others, the capitalist may protect himself by hoarding or may even find profit in the fluctuations of values; but the wage earner … is practically defenseless. He relies for work upon the ventures of confident and contented capital. This failing him, his condition is without alleviation, for he can neither prey on the misfortunes of others nor hoard his labor.

The parallels to today are unmistakable, absent only an eloquent head of state.

Unless a proper defense is mounted, the squeeze will be put on workers until profits recover. Depressions intensify the misery of working people and recoveries only happen at their expense. When workers are footing the bill, Business Enterprise will spare no expense in wages, health, or lives.

Several years ago, I was browsing the Library of Congress newspaper archives for first-hand accounts of the turbulent days leading to the Great Depression of 1873-96. The following story was published in The Sun on the day the New York Stock Exchange was shut down to ease the panic. I’ve transcribed it and posted it here for your edification.

The Sun

New York, Saturday, September 20, 1873

A Bewildering Spectacle at the Fifth Avenue Hotel Last Evening.

The scene at the Fifth Avenue Hotel last night was bewildering. As early as five o’clock brokers, whose wet coats showed them to have come directly from Wall street without taking time to change their clothing, entered hurriedly, and gathering in small groups throughout the corridors, anxiously discussed the disastrous events of the day. At eight o’clock the crowd on the sidewalk for half a block on either side of the hotel was so dense that it was difficult to make a passage through it.

A solitary newsboy who proclaimed the failure of the Fourth National Bank was for a moment invested with all the importance of the Vice-President of the Stock Exchange when reading to the bulls and bears the letter announcing the regrets of such and such a firm at being unable to meet their engagements. It was listened to in breathless silence for a few seconds, and then a proposition was made to hold him on the track while the wheel of a University place car passed over his head. He retired for a time, but was afterward heard in the neighborhood of the Hoffman House announcing the failure of many well-known banks and business firms, until he was led away by the ear by a policeman [The newsboy was right. There had been a run on the Fourth National Bank. — GM].

The pavement for some distance from the sidewalk was not unlike a duck pond, but well-dressed men, with much speculation in their eyes, stood ankle deep in the slush apparently with as much indifference as though a well-padded Brussels carpet was under their feet.

Inside a stranger might have been led to suppose that a fair, much more popular than such enterprises usually are, was in progress. Men whose husky voices testified to the vigor of their recent efforts in the Stock Exchange, and men whose muddy boots were no less indicative of their more humble labors on the street, mingled amicably on a neutral floor of the great hotel. Toward the upper end of the hall the crush became greater, until above the office it was hardly possible to move at all. Fortunately a sort of safety valve was found in the

BARROOM

door, and into this the multitude poured by dozens, to emerge in ten or fifteen minutes considerably cooler and disposed to take a much more cheerful view of the financial situation than when they entered. The barkeepers were sorely tried, and it was rumored that one of them was becoming delirious, a report which was said to have emanated in his concocting a sherry cobbler when a mint julep was called for. There was not a great deal of business transacted, for although many were there who evinced a desire to transform the hall into a temporary Stock Exchange, the greater number seemed to feel that it would be more politic to reserve all their energies to meet the exigencies of the coming day. The extraordinary collapse of so many prominent houses in so short a time had predisposed men to give credence to reports which at any other time would have been laughed at as clumsy falsehoods, and the wildest rumors regarding the failure or suspension of other and larger firms gained circulation. Nearly half the banks in New York were at one time or another in the course of the evening said to have collapsed. The general impression was that many of the banking institutions, especially those for savings, would be obliged to sustain a run to-day.

The scene in the reading room was very animated; every chair had its occupant, and as many as could find room sat on the tables. Each man was perusing the latest edition of some newspaper, and the manner in which interesting paragraphs were read aloud to persons who paid not the least attention to them, but were themselves reading something to a friend who was equally indifferent, and anxious only to be heard by someone else, formed a curious Babel of sounds, more novel than intelligible.

Within their mass partition the wearied telegraph operators were working like bees; not a minute’s respite was allowed them, and the monotonous click, click of the instruments was heard until midnight. Every inch of the desk outside that could be made available for writing purposes was in use, and behind the first row who leaned over it was another standing with the printed forms in their hands waiting for an opportunity to write despatches. Even

THE BARBER’S SHOP

was turned into a debating room, and men leaning back in the chairs – their faces covered with snowy lather and their forms enveloped in flowing robes seized every opportunity offered them of talking, without absolutely endangering their jugulars, to give expression to their opinions regarding the events of the day, and, in view of the short space of time allowed them during the wiping of the razor, speaking so rapidly as to be utterly unintelligible. Men who were having their hair cut had a great advantage over those being shaved, and used it to the manifest uneasiness of the latter.

A few restless spirits had collected in the billiard room, and endeavored to forget their cares in the excitement of the game, but they flourished their cues in a manner more indicative of demolishing the lamps than of making a run. Misses, which might otherwise have been unaccountable, were accounted for by the explanation of the player that he was out of practice.

At half past 9 o’clock confidence was in some measure restored by the appearance of Col. Spencer. He was not in full uniform, being, indeed, attired in a rather damp black frock coat. His features bore an expression of placid calmness, and even the most timid, looking upon him, praised God and took courage. He was leaning upon the arm of an aide-de-camp, who was also out of uniform, and as the two passed slowly up the hall they were followed by many an eager eye, and the aide-de-camp, shining with a reflected light, came in for a share of the admiration.

Toward 11 o’clock two gentlemen, probably from the rural districts, entered, and were much surprised at the throng which filled the hall. One of them asked the clerk if there was any special reason for this gathering. He was informed that it was caused by some slight financial entanglements in Wall street.

“HOW MANY HOUSES FAILED TO-DAY?”

asked the gentleman. He was told that several had succumbed to the storm, including the great house of Fisk & Hatch. The same gentleman then took up an evening newspaper of Thursday which was lying on the desk, and seeing the announcement of the suspension of Jay Cooke & Co., he asked whether it was true. The clerk laughed, and the second gentleman, who had not yet spoken, now said, with contempt, “Pshaw, man, you must have been asleep; why, I knew that an hour ago.” A hearty laugh from all within hearing greeted this instance of information promptly received.

Henry Clews entered about 9 o’clock, and was instantly surrounded by a number of eager questioners, who hung upon his words as though they were the utterances of a prophet. He remained about an hour.

Noticeable in the throng were: John F. Tracey, B. F. Carver, H. N. Smith, M. L. B. Marin, Harvey Kennedy, John R. Garland and his partner Mr. Seeley, Mr. Cecil, Mr. Clark of the firm Clark & Walton, G. J. Haven, Wm. Heath, A. Hendrix, and many others.

Every room in the hotel was occupied, and late comers were obliged to be content with a bed in one of the parlors.

About 11 o’clock the crowd began to decrease, and by midnight the hall was deserted.

Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Library of Congress, http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/

Transcribed by Geoff McCormack

[…] Continue reading here. […]

LikeLike